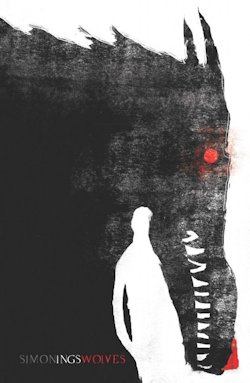

Wolves has been hailed as Simon Ing’s “spectacular return to SF,” and it is that, I think—though the text’s spare speculative elements only come into focus in advance of the finale, when the augmented reality Conrad’s company conceives of matures into something more meaningful than an idea.

The rest is something else: a catastrophic coming of age tale complicated by a macabre mystery which reminded me of This River Awakens. At the book’s beating heart, however, is the frustrated friendship between Conrad and his schoolmate Michel:

Michel was quiet, lugubrious, self-contained. For me, at any rate, he had extraordinary presence. A glamour. If he understood my feelings for him, he never let on. He showed very little tenderness for me. He wasn’t interested in my weaknesses. He wanted me to be strong. He cared for me as you would care for your side-kick, your familiar, for the man you had chosen to watch your back. He said we had to toughen up.

For what? Why, for The Fall, folks!

“The End Times were on their way. [Michel] was convinced of this.” Conrad isn’t so sure, but he plays along with his hero’s apocalypse prep—both to be with him and to escape the hell of his own home, an Overlook-esque hotel with an equally unsettling clientele: war veterans who were blind before our central character’s father equipped them with special sensory vests.

All of which comes into play in a major way later, but at the beginning of the book, it’s background. At the foreground of this phase of the fiction is Conrad’s manic mother: a woman who habitually abandons her family in favour of “a protest camp that had grown up around a nearby military airbase.” She has to be rescued from this retreat repeatedly—a pattern rudely interrupted one summer when Conrad discovers her dead body in the boot of his father’s car.

To his untrained eye, it looks like a suicide, and so, realising what a blow it would be to steal his mother’s thunder, he acts as if nothing has happened, and waits for his father to find her, sure this is what she would want. Too soon, however, he starts second guessing himself. A series of ghastly pratfalls follow as a confused Conrad tries to contrive a crime scene around her corpse.

The consequences of this decision will haunt him through adolescence and into adulthood—which brings us to Wolves’ second section: a near-future narrative in which Conrad and the object of his unrequited affection reconnect after a decade of deliberate distance.

By now, both of the boys have settled into straight relationships. Conrad gives up on his the moment his former friend calls, and speeds off to spend some quality time with Michel and his partner Hanna. What he finds when he arrives at their place shouldn’t be a surprise… nevertheless, it knocks him for six:

They’re living through a little Fall here, ’saving on bills,’ taking baby steps in readiness for when the lights go off for real, forever, and the telephones stop ringing, and the pipes go cold and brittle, and the only water’s rain which they must boil.

I should not have come.

Before long Conrad is caught between memory and imagination, “pressed against a past I am afraid will swamp me” and a future on the edge of the End Times Michel has fantasised about from the first.

Brief as it may be, Wolves is an abominably ambitious book which reinvents itself endlessly to truly tremendous effect. Ings’ vision of the collapse of civilised society is seductively simple: his is a piecemeal apocalypse brought into being incrementally, by way of a succession of indiscretions as opposed to some common or high concept plot point like global warming or unchecked epidemic. On the other hand, his ideas about immersive technologies—about aerosolised AR and fictional “characters who’ll share your breakfast coffee”—are big, bold, and impressively fully fledged… albeit treated with the same restraint Ings applies to the novel’s two milieus:

“This stuff’s just the scene-setting, the research. In the end, so long as important bits of it are parked in the back of your head, none of this world-building nonsense matters. But I thought you’d like to see it.”

I did indeed.

Wolves works exceptionally well as a mystery, additionally, suggesting certain tensions early on, advancing our understanding of them slowly but surely over the course of the whole, before ending on a surprise that is satisfaction itself in its drawing together of disparate elements from narratives past and present. In the interim, Ings offers up an affecting yet refreshingly unsentimental exploration of friendship and fidelity, all lies and ties.

It’s a little preachy, perhaps, and women—be warned—are not well treated in the text, but Wolves succeeds on so many levels that it’s clear we’re looking at one of the best books of the year, here: a gripping cross-genre odyssey as dark as it is smart.

Wolves is available from Gollancz on November 13th in the UK, and May 1st in the US.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.